by Julia Travers

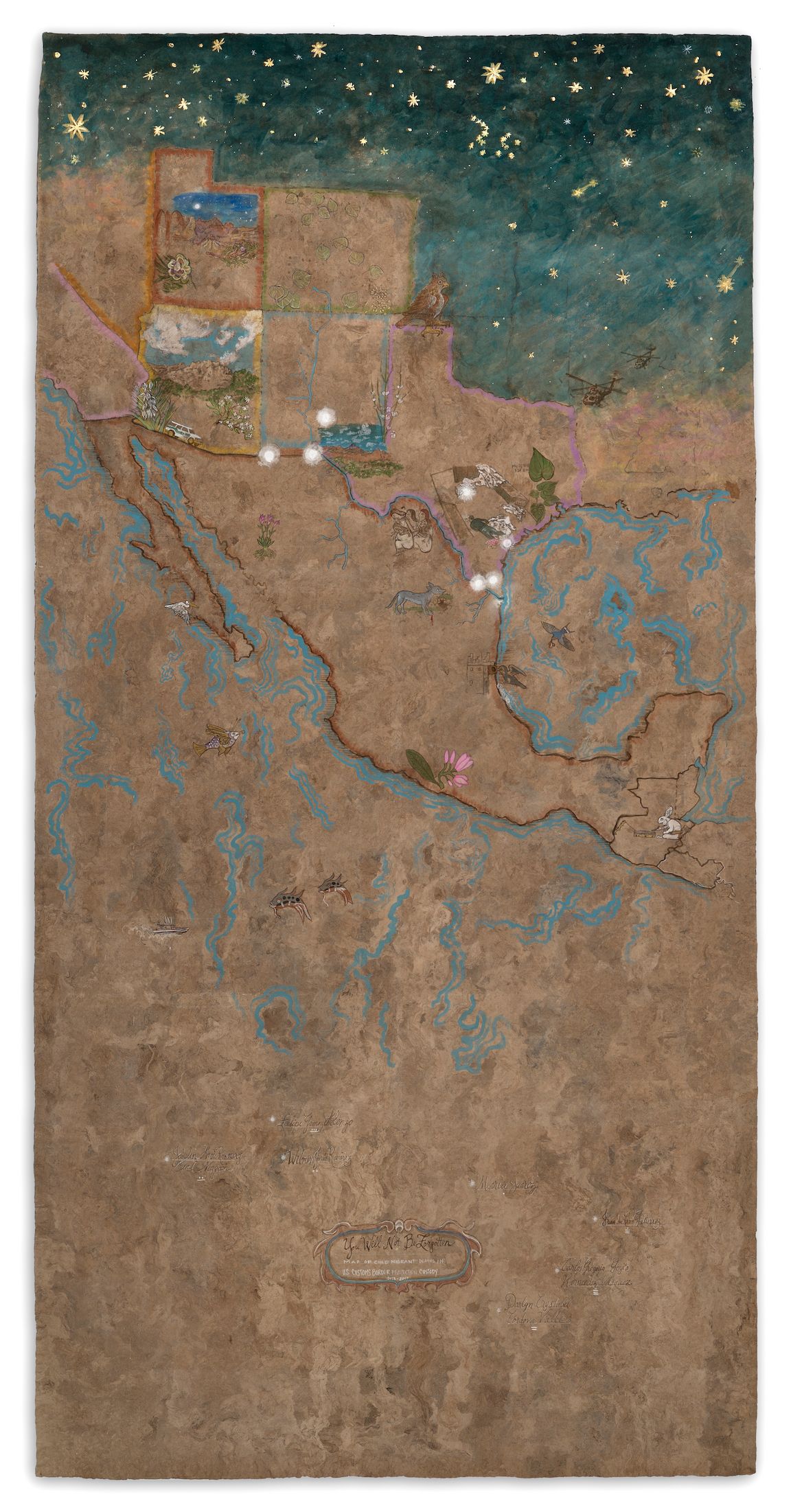

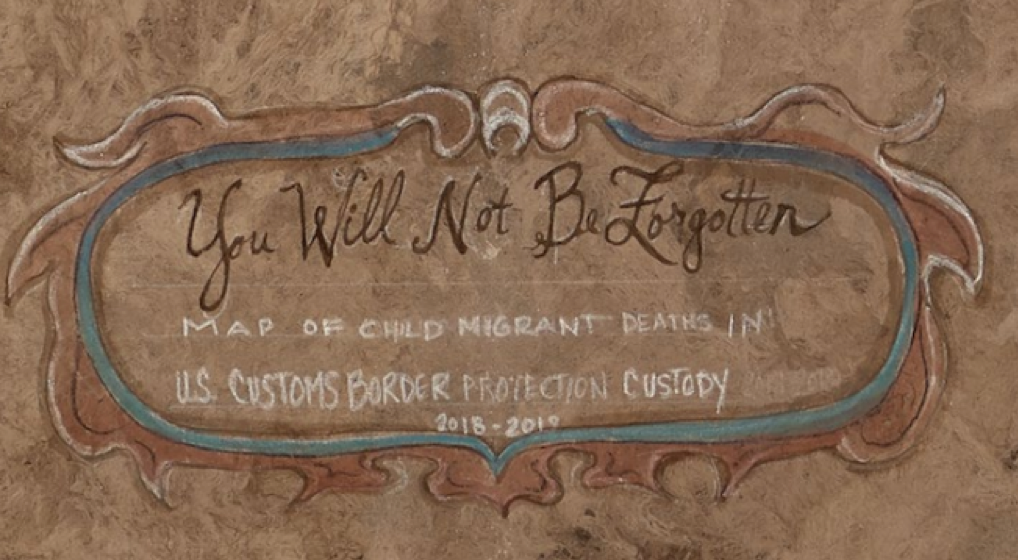

“You will not be forgotten,” artist and educator Sandy Rodriguez promises the seven children portrayed in her recent art show at the Charlie James Gallery in Los Angeles. These Central American child migrants all died in U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) custody during 2018 and 2019. Rodriguez, who is institutionally trained and also comes from a family of Mexican artists, painted each child as part of a larger series called Codex Rodriguez-Mondragón (after her father’s and mother’s surnames).

In 2021, 500 years will have passed since the conquest of Mexico. Rodriguez’s art examines how much and how little has changed in that span of time. “Here we are, 500 years later, with a lot of similar kinds of violence on Indigenous bodies, violence on communities that have inhabited or have inhabited this region for thousands of years,” Rodriguez says. Her works explore this enduring trauma, and honor and reanimate Indigenous traditions and knowledge.

Her Codex references, in part, the 16th century Florentine Codex, which was created by a Franciscan missionary and Indigenous scribes writing in Spanish, Latin and Nahuatl (the Aztec tongue). It served as an aid for colonizers and is also now a crucial and singular documentation of pre-colonial life. Rodriguez also draws from the colonial-era medicinal manuscript Codex de la Cruz-Badiano, which an Indigenous doctor wrote as he endured the 1521 conquest and subsequent plague. Rodriguez follows in the steps of other Chicanx artists who have created their own time-transcendent codices in response to these kinds of historic texts. She sees herself as a tlacuila— a Native scribe.

The Codex Rodriguez-Mondragón consists of maps, portraits, ephemera and other elements that explore and document lives, losses and culture along the U.S. borders. Rodriguez, who has family on both sides of the border, has carried out years of research into the history of these lands, the botanical makeup of their ecosystems, and ancient creative practices that endure.

Her works are made of natural materials including handmade, traditional dyes and a Mexican paper called amate, crafted from mulberry bark and various species of ficus. The Spanish were known to burn works on amate, which signaled Indigenous cultural transmission. She uses cochinilla (a bright, pre-Columbian red pigment), orchid bulbs, insects, gold leaf and other natural materials to create a family of works that weave together witnessing, mourning, honoring and revival.

The names and ages of the seven children Rodriguez memorialized with portraits are:

Mariee Juarez, who was one when she died.

Carlos Gregorio “Goyito” Hernandez Vasquez, who was 16.

Wilmer Josué Ramírez Vásquez, who was two.

Juan de León Gutierrez, who was 16.

Felipe Alonzo Gomez / Felipe Gómez Alonzo (different names were given by the LA Times and CNN), who was eight.

Jakelin Amei Rosmery Caal Maquin, who was seven.

Darlyn Cristabel Cordova-Valle, who was 10. She died in 2018 and her death was the first child death in CBP Custody since 2010.

Most of these children died from communicable illnesses in overcrowded CBP detention facilities in the Southwest. While researching this series, Rodriguez says the “field study takes place in the spring, when families and children are being caged underneath the freeways in El Paso. The images are circulating. By the time I drive a thousand miles from Arizona into El Paso, they'd already moved the families. Amongst those families are children like Felipe Alonzo-Gomez, who died just a few weeks later due to heat.”

Rodriguez’s Codex series contains a large, about 8-foot-tall map that shows the detention centers where the children died. It also includes a pictorial recipe drawn from the historical medicinal codex, which describes how to heal susto, or trauma. Icons show where plumeria flowers, fox blood, swallow’s nests and other ingredients can be found in the local landscape surrounding the centers. A Charlie James Gallery catalog states: “Ix Chel and Tenten In na are the grandmother goddesses from the Mayan and Nahua pantheons, and they flank the sides of the map. Both deities are associated with medicine, medicinal herbs, healers and midwives, and are summoned to watch over us and these children on their journey to the land of the dead so that they can return to visit next fall and every fall.”

In 2018, in a moment that seems prescient of the COVID-19 pandemic, which places detained immigrants at great risk, Rodriguez spoke of the scribes who created the Florentine Codex with the LA Times. “There is a massive plague that happens at the end of the book… And they’re all dying, so they can’t go out and get color, and so everything is black and white. They end up sequestering themselves so they can tell their story.” She added that a sense of the world ending carries forward into our current era.

She tells us the “human rights crisis at the border is still ongoing … We still have 70,000 children caged across the U.S. There's still unaccompanied minors going to court and making decisions on their own.”

These enduring struggles drive Rodriguez’s work. She hopes “something will occur in viewers to inspire them to ask more questions, have more conversations, take some action, register to volunteer -- to do something with that experience.” At a walk-through of the LA show, she invited the Young Center for Immigrant Children’s Rights “to tell [attendees] about the upcoming training days, so they could find out how they could become involved in child advocacy, or how they could be of support.”

Rodriguez will also display one of her works in June at the Denver Art Museum. She continues to observe, learn, dig, record, collaborate, alchemize and make, offering visual expressions that bridge time, space, language and culture. She is propping a door open for us so that we may encounter, honor and better understand the lives of and crimes against Indigenous peoples and immigrants, and hear the voices of Native foremothers and fathers; she is translating their journeys into living maps and holding space for all of us to enter.

Cover art: Sandy Rodriguez, paintings of Juan de León Gutierrez and Darlyn Cristabel Cordova-Valle (image courtesy of the artist and Charlie James Gallery, Los Angeles, photo by Michael Underwood)

Julia Travers writes news, analysis and creative pieces. She often covers science, social justice and the arts. Find more of her writing at jtravers.journoportfolio.com or on twitter @traversjul.