Poetry by Ana M. Fores Tomayo

Two years ago on World Refugee Day, I published a very personal essay about my status as a refugee child, back then, yet what it is like now for refugees and asylum seekers. Today, I publish my own poem — in its original Spanish followed by my English interpretation (because translation is never poetry!) — about the plight of the asylum seeker, so that we know.

So that we can be witness to our own ungodliness.

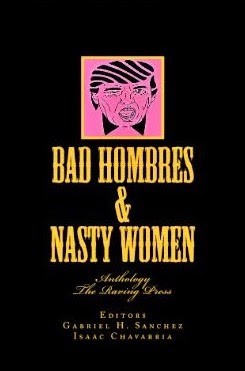

The English version was published in Bad Hombres and Nasty Women, from The Raving Press: if you would like to buy it, go to this link. There are many other great works in this little treasure! But I wanted to print the Spanish original too, so I am publishing both versions here *now, *the English below the Spanish.

Refugiado

Mi alma en pedazos,

Veo el alambre de púa

rasguñando metal contra piel.

Llorando lágrimas de sangre,

Escucho disparos al vacío del silencio

de la Salva Maratrucha.

Lo empujo bajo la cerca

pero llora mi hijo,

aunque no importa;

lo hago porque

lo quiero.

Caminamos caminamos…

horas por las vías podridas

de los coyotes,

días, semanas, un mes, mano en mano:

vamos enfermos,

sin comer,

sin beber,

sin hablar.

O cuando hablamos es llorando,

porque no hay energía para más.

¿Dónde se habrá ido la niñez de mi hijito?

¿Cuándo la perdió?

¿Será cuando vio a su tío caer por unas balas

que le correspondían a su madre?

La eternidad del infierno

ha pasado en frente,

y cruzamos la frontera

llegando al río.

Atravesamos en balsas,

yo muerta en vida

con mi hijito en brazos.

Nos damos por vencidos

en esa tierra de tinieblas

y nos tiramos a sus pies —

esas patrullas sin cara, sin rostro.

Les decimos, susurrando,

“tengo miedo.”

II

Recuerdo los ojos negros

de mi hermano,

entreabiertos, glaseados,

la sangre estallando sus entrañas,

mi abuela gritando

corre, niña, corre,

eres tú la que quieren,

es tu sexo,

tu poder como mujer,

tu manera de decirles no.

Oigo los disparos lejos todavía,

y vuelvo a escuchar la voz de

mi querida abuela:

vete con tu niño antes

que te maten, dice.

Y el presente rompe pesadillas

que me trae aún más asaltos:

percibo a un guerrero,

llama en llamas…

el choque me catapulta hasta la actualidad.

La policía fronteriza me pregunta,

“¿Regresarás?”

Y yo le digo, con sarcasmo,

“Quiero ver mi patria,

quiero oír los

tiroteos tormentosos,

quiero ver las maras

asaltando uno al otro,

mata mata.

Quiero ver mi hermano muerto,

quiero ser luceros de mi abuela

llora llora.

Quiero ver la sangre deslumbrar

lo verde en las montañas,

las piedras de mis calles,

el agua de los ríos,

pero todo rojo rojo

Sangre sangre

Llora llora.”

“Corre, niña, corre:

eres tú la salvación.

Llévate a tu hijo,

líbralo de este horror”.

Así es que oigo esa voz tan asustada,

las palabras apocadas de mi abuela,

pero no me quiero recordar…

¿Qué te pasa, chica?

Pregunta el agente de mal manera.

Tengo miedo, Policía.

Tengo miedo.

Pero igual, no me quiere escuchar.

III

Me agarra fuerte, recio,

maltratándonos el hombre ICE.

Nos tumba, belicoso.

Se cae de mi protección mi hijito tembloroso.

Nos arrastra, ese monstruo,

forzándonos hacia deslumbrantes luces:

refulgentes, cegadoras,

dando vueltas sobre un carro.

Nos encarcela en el perrero

con sirenas estridentes,

con barrotes enrejados,

¿ese furgón no es hecho para perros?

Pero no.

Entre ropas empapadas por el río congelado

y el crítico engaño de un hueco reducido

en que los vigilantes nos encierran,

llegamos a una celda fría,

insensible,

aséptica, estéril:

desinfectada de piedad total,

y así nos hielan a los dos,

abrazados uno al otro,

mi hijito y yo.

El calor entre madre e hijo

siempre es suficiente para quitar

el frío inhumano de agresores asaltantes,

pero no es suficiente para desarmar

espíritus perversos,

para darle miedo al más malvado.

Me acurruco con mi hijo,

y lloro lloro…

IV

Llegamos a nuestra celda

con otras madres, otros hijos indefensos.

Oh, las luces fluorescentes chillan

día y noche.

Las comidas recuerdan asco.

No hay vida

más allá.

Los guardias nos desprecian,

tratan de humillarme

como si fuera yo

la que hubiera hecho el crimen,

como si fuera yo

la que hubiera herido

a mi hermano

en vez de la que corre

por su vida…

Y presiento a mi hermano

todo un hombre,

un recuerdo

con corbata de cielo azul,

cerúleos susurros quietos

vestido con traje de lino blanco,

mientras camina él, despacio, inocente,

con piernas de un roble eterno.

¿Pero será ésta

la memoria de mi hijo,

o es la de mi hermano vuelto en vida?

¿Será éste un sueño

de aquí o de más allá?

V

Pasan meses en un sinfín

de agonías,

una monotonía de días rutinarios

donde nada pasa,

porque todo es mentira,

todo es artificial,

todo es locura.

Por fin nos toca hablar

frente a un tipo comisario,

oficial del maquiavélico ICE

para explicar mi miedo.

Este nos mira indiferente,

me dice sin creerme,

¿Porque estás aquí, chiquilla?

¿Vienes a robarnos la comida?

Y yo pienso en mi hermano,

muerto sangre fría,

un batallón de drogas

despojando mis bellas tierras

para llegar a este espacio libre,

y yo pienso en la vegetación

que ellos devastaron

para hacer lo que arrasa

hoy en día

a mi país sagrado.

Pienso en las tierras,

en las vidas,

en la sangre que me roban…

en mi hijito,

en mi hermano muerto,

en las mujeres que nos violan,

en mi pueblo amado,

en mi patria destruida.

Y entonces veo a la migra,

miro al funcionario,

ese hombre que trabaja para ICE,

preguntándome con desdeño

si los pienso atracar,

y les contesto, fría:

Sí, ya que ustedes están aquí

burlándose de mí,

vengo justo para vindicarme

yo de ustedes.

Vengo a que sufran admirando

mi criminalidad,

soportando esa culpa de comprender

todo, todo mi dolor.

Fíjense:

la mujer violada, su hermano muerto.

Contemplen estas transgresiones,

las amenazas, la miseria,

las matanzas, la muerte en vida:

ésto es mi país querido.

Y entonces, recuérdense de mí —

detalle por detalle;

reflexionen en lo que represento,

y memoricen estas lágrimas de sangre

cuando se rían de todo refugiado.

Refugee

My soul into pieces,

I see the barbed wire

ripping metal against skin.

Crying tears of blood,

I hear gunshots in the vacuumed silence

of the gang’s Salva Maratrucha.

I push him under the fence

but my son cries.

No matter:

I do it because

I love him.

We walk walk walk…

hours and hours on the rotted roads

of the Coyotes,

days, weeks, a month, hand in hand:

we go, sick —

without eating,

without drinking,

without speaking.

Or when we speak, we do so crying,

because there is nothing left for more.

Where did my little son’s childhood go?

When did he lose it?

Is it when he saw his uncle fall by a bullet

meant for his mother?

The eternity of hell

has bridged our path,

and so we cross the border

reaching the river.

We travel in rafts;

I am the walking dead

with my little son in my arms.

We give up

in that land of darkness

as we throw ourselves at their feet —

the faceless border patrol: no image, no semblance.

And I say, whispering,

“I am afraid.”

II

I remember the black eyes

of my brother,

parted, glazed over,

blood bursting his bowels,

my grandmother screaming

run, girl, run,

It is you they want,

it is your sex,

your power as woman,

your way of saying no.

Still I hear the distant gunfire

as I listen to the voice of

my grandmother once again:

go with your child before

they kill you, she says.

And the present shatters nightmares

that produce even more assaults:

I perceive a mercenary,

burning flames…

Shock catapults me to the present.

Border patrol interrogate me,

“Will you return?”

And I say, sarcastically:

“I want to see my country,

I want to hear the

raging shootouts,

I want to see the maras

assaulting one another,

kill man kill.

I want to see my dear dead brother,

I want to be my grandmother’s star of light

crying crying.

I want to see the blood bedazzle

the green of my rugged mountains,

the stones of my pebbled streets,

the river water flowing,

but all is red red

blood blood

Cry cry.”

“Run, girl, run:

you are our only salvation.

Take your son away,

deliver him from oh, this horror.”

So I hear that panicked voice,

my grandmother’s dreaded words,

but I want never to remember…

What is it, girl?

Asks the agent, mean and foul.

I am afraid, Policeman Sir.

I am afraid.

But still, he does not want to hear.

III

He grabs me strongly, with brute force,

bashing us, this bully ICE man.

He knocks us down, thrashing, bellicose.

My son falls from my protection,

my trembling little boy.

He drags us, this inhuman monster —

forcing us toward the glaring lights:

incandescent, blinding,

their flare piercing round and round.

He imprisons us in an old dogcatcher

screeching sirens screaming,

slatted with thick metal,

Is this cop car made for dogs?

But no.

Cloaked in clothes drenched by an icy river

and the key deception of the dwarfed hole

to which the armed guards cage us,

we arrive at a bleak, sterile prison:

insensible, aseptic,

sanitized of all damned godliness,

they freeze us both

while we embrace each other,

my little boy and me.

The warmth of mother and son

is always enough to take away

the cold from smiting bastards,

but not so when it comes to disarming

perverse spirits,

to striking fear in the most evil.

I huddle closely with my son,

crying crying…

IV

We arrive to our cell

with other mothers, other defenseless children.

Oh, fluorescent lights wail

both day and night.

Meals reminisce disgust.

There is no life

beyond today.

The guards despise us,

try to humiliate me

as if it were I

who would have done the crime,

as if it were I

who would have hurt

my brother

instead of the one who’s running

for her life…

And I sense my brother

all a man,

a memory

with blue sky tie,

cerulean whispers

dressed in bleached white linen.

Then I watch him walk away

slowly, innocently,

with limbs of timeless oak.

But is this

the memory of my son,

or is this my brother come alive again?

Will this be a dream

from here or from beyond?

V

We spend months in a cornucopia

of agonies,

a monotony of routine days

where nothing happens,

because everything is deception,

everything is artificial,

everything is mad.

Finally comes the day when we talk

to a commissioner,

an official of that machiavellian ICE:

we must explain our fear.

This man looks at us indifferently,

tells me, not believing,

Why are you here, girl?

Have you come to steal our food?

And I think of my dear brother,

slaughtered, in cold blood,

a battalion filled with drugs

despoiling my sacred land,

yet surfacing in this free expanse,

and I think of the vegetation

they demolished

to undertake what ravages

my country

nowadays.

I think of the land,

of the lives,

of the blood they steal from me…

I think of my son,

of my dear dead brother,

of us — the women they have raped;

I think of my beloved people,

of my homeland — wrecked, destroyed.

And then I see the migra,

I look toward the agent,

those men who work for ICE,

asking scornfully

if I think I might assault them,

so I tell them, bitterly:

Yes, since you disdain

to mock me,

I come explicitly for vengeance.

I come so you can suffer

delighting in my criminality,

I come so that you understand

that guilt, of oh, so much my pain.

Beware:

the woman raped, her brother dead.

Contemplate oh these transgressions,

the threats, the misery,

the massacres, the death in life:

this is my beloved country.

And then, remember me —

detail by bloody detail;

reflect on what it is I represent,

and memorize these tears of blood

when you laugh at every refugee.

*Originally published in Spanish and English on the blog Adjunct Justice.

***All Photos credited to Ana M. Fores Tamayo.

Being an academic who was not paid enough for my trouble, I wanted instead to do something that mattered. Thus I began to advocate for marginalized refugee families from Mexico and Central America.

Working with asylum seekers is heart wrenching, yet satisfying. Their pain, their sorrow, their joy, is quite humbling. Moreover, being with them has helped me with my own sense of displacement, since I too was a child refugee, trying to find a new home.

But this is the refugees’ life today: I have seen it, I have heard it, I have cried tears with them through every phase. I have sat in the court rooms as they await news of their most definite deportation, and now I want to share their agony with the world, so that we realize it might not have to be this way…

I write as an expiation, to banish my demons, so that I can continue my work.