by Joseph Sorrentino

Noel had been walking for about ten hours when we met him on the narrow dirt path that parallels the train tracks in Chahuites, a small city in the Mexican state of Oaxaca. The path he was walking on is the one that virtually all Central Americans take on their way to the U.S. When he first saw us, he turned away and it looked like he was going to run — there were eight of us and he told us later he thought we were a gang out looking to rob refugees — but Carlos called out to him and explained we were from the shelter and would take him there.

When I got up early the next morning, I found Noel sitting on a low wall in the shelter, his backpack at his feet. I thought about beginning the interview but decided to wait a bit; let him at least have some breakfast, I figured. So I sat a few feet away. A minute or so later, he strapped his backpack on and walked out the front gate of the shelter. I followed and watched him, wondering why he walked out when breakfast would be served soon. Then another kid about the same age and carrying a backpack approached Noel and without exchanging more than a simple nod of the head, the two of them starting walking down the road. At first I thought they were going to the small store next to the shelter but they walked past it and, at the corner, turned, heading north. They were on their way to the U.S.

I beat myself up pretty good for a couple of days. I cursed myself for not getting his story. I decided I have to be more aggressive getting interviews. Next time, things would be different. Then I realized his actions told me far more than any words could have. So desperate was he to get to the U.S. to help his mother, he refused to wait those few minutes for breakfast.

Last Night in the Shelter, Menores en el Camino

I finally connected with several guys — amazing what a Coke and a couple of sueltos can do for a guy — and things started to go well. But the noise is amazing — screaming just for fun, pounding on the stairs, a long, shrill whistle. And bone-jarring rap music until 10 at night. It all got to me; I felt resentful. Then, tonight, one of the guys got cut in a fight. I saw blood on the second floor landing and called Carlos and he told me what happened. Fortunately, it was only a cut on the small finger of his right hand but it still required stitches. It was Alcides, one of the quiet guys, which was very surprising. David, the volunteer from Hungary, told me Alcides refused to get an injection; probably tetanus or an antibiotic. They tried to convince him but he refused.

Tonight, none of the guys are downstairs like they usually are. They’re up on the third floor, right above me, blasting rap music. I went out to the balcony but it was only marginally better. I thought about their lives, what they faced, what they face here and what they’ll face as they continue their journey. Oddly, the rap doesn’t bother me tonight.

Margarita

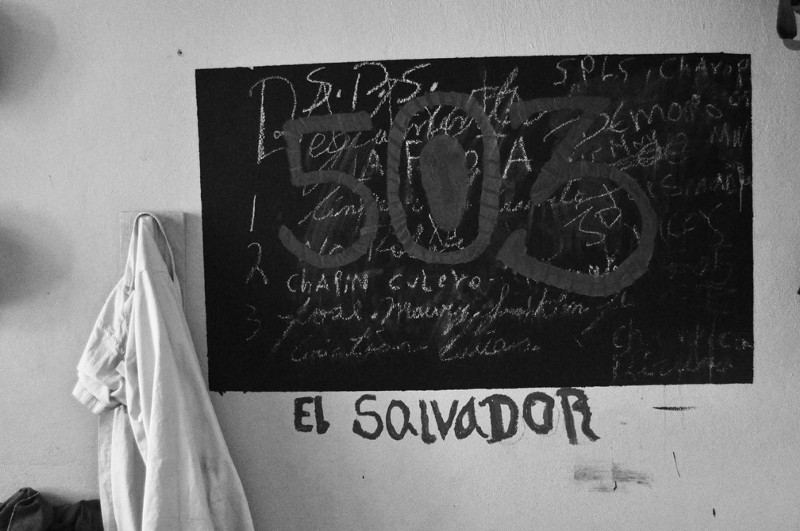

Margarita is an 18-year-old Salvadoran with a pretty face and ready smile who left home after she and her family were threatened by one of the Maras. She says the gang wanted money and that, “me molesta:” They bothered me. She says this with no emotion, a slight glance downward betraying its possible meaning. I ask David, a volunteer who’s helping with translations, if she means they threatened or tried to rape her. He nods his head, “yes.”

Like many Central Americans, she’s traveling through Mexico without any papers that legally allow her to do so and, like the others without papers, keeps a sharp eye out for Mexican immigration officers. She’s been fortunate not to get caught, although she has seen them on occasion. She knows if they catch her she’ll be deported and if that happens, she faces danger in her home country. If it happens, she says, “I’ll just try again.”

This morning I find her sleeping on a worn mattress placed on the floor next to the large, wooden kitchen table. I ask her why she does this and she says it’s because it’s cooler; there’s a window just above where she slept.

Her plan is to eventually continue on to the U.S. to reunite with a sister in San Francisco. She says she’ll work cleaning houses, babysitting. Doesn’t matter. Whatever work there is, she’ll do. When asked how she’ll get into the U.S., she answers quickly with one word: “However.”

She’d stayed in another shelter before coming to Oaxaca and I ask her if she likes this one better. She says she does. “Es mas bonita.” It’s prettier. This, a shelter layered with dirt, with trash piled high in the yard behind the kitchen, marginally functioning bathrooms, where she sleeps atop an old mattress on the floor. Prettier. But I suppose compared to what she’d face back home, even hell might look prettier.

Joseph Sorrentino is a freelance photojournalist whose work has been published in In These Times, The Santa Fe Reporter, and Commonweal.

**View more of his work at: **http://www.sorrentinophotography.com/index.htm

Contact: joso1444@usa.net