by Rachel Melancon

“But one lesson the Holocaust should have taught is that we can’t hesitate to name the inhumane.”

I had a conversation with my mother recently about language. She said, to her knowledge, her generation didn’t like to label things in black and white. You just didn’t say that something was good or bad. You didn’t make value judgments. It’s one of many communication pits between generations.

"The specific language of one atrocity becomes polarizing and so emotionally charged that we set it aside and reinvent language for the next time, and thus avoid any direct comparisons or challenging questions."

When I called detention centers “concentration camps,” echoing a Congresswoman, my uncle was flustered and upset because to him, that phrase is limited to the Holocaust in Europe and anything adopting that phrase must be equal to or greater in scale. The specific language of one atrocity becomes polarizing and so emotionally charged that we set it aside and reinvent language for the next time, and thus avoid any direct comparisons or challenging questions.

This is how we avoid eye contact with our victims.

We don’t like words, or labels, or judgments. They’re upsetting. They’re challenging. They turn into arguments about definitions and nuance and historical precedent and anything other than the actual topic at hand. That’s why we have euphemisms, or why we steal outright from other languages. The words themselves, the sounds on our tongues, are less upsetting that way.

This is how we turn our heads.

"Use and abuse of language, through euphemisms and borrowed words, is how we code evil and suffering in a way that does not trigger our collective conscience."

Use and abuse of language, through euphemisms and borrowed words, is how we code evil and suffering in a way that does not trigger our collective conscience. It is how we sleep at night knowing that down the street, a mother sobs for her infant son, and another block down, that infant is screaming in fear, hunger, and confusion all by himself because a man didn’t feel like keeping them together. It is how we distance ourselves from a little girl trying to make herself look plain so that she won’t be bought as a sex slave for men three times her age. We just call it business decision and fancy trade.

"By the time organized human rights abuses reach general awareness, the general ear has already been trained to disregard it as normal."

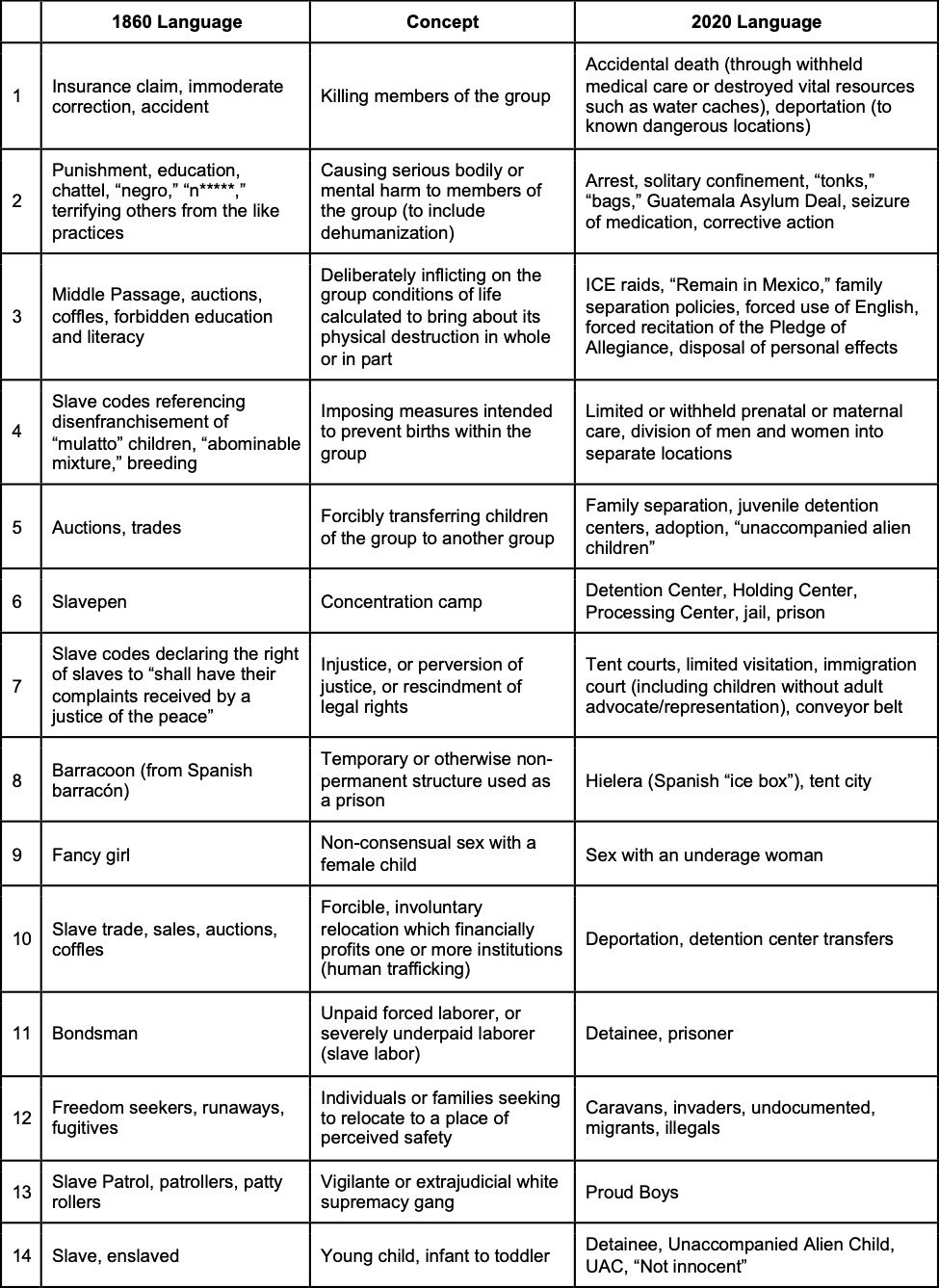

The primary function of euphemisms in the table below is to depersonalize and dehumanize; in other words, to reduce the victims (those who are suffering) to objects, and simultaneously absolve the abusers (those inflicting the suffering) of moral or legal guilt. This is how human rights violations on mass scale are allowed to happen: by the time organized human rights abuses reach general awareness, the general ear has already been trained to disregard it as normal.

This is how we don’t hear the screaming.

Euphemisms, particularly very technical euphemisms, groom the public for moral disengagement and rationalization. You may recall having heard someone patiently saying, “but slavery was legal at the time,” and is, ostensibly, thereby okay. Euphemisms and cleverly crafted phrases create the laws by which we excuse our behavior.

“Just following orders,” Peter von Hagenbach said in his 1474 trial for war crimes.

Maybe if we have to use euphemisms to discuss it, we should not be doing it. If we can’t call evil by its name, maybe we should not accept its money.

This essay series explores the structural parallels between the American slave trade circa 1860 and the American immigration/deportation system circa 2020. It does not presume to tell the stories of enslaved or incarcerated individuals or to compare or equivocate the suffering of nineteenth century African Americans and twenty-first century immigrants. It does not intend to erase Native American trauma through omission; this is about how the South, as a region, as an economy, was designed to concentrate a given people and then forcefully locate them elsewhere. It first experimented with Native Americans on the Trail of Tears, liked the results, reached economic peak with African Americans, and still runs quietly on the backs of immigrants.

Author's note: Rows 1-5 concepts are taken verbatim from the United Nations Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, or General Assembly Resolution 260, from which the US has declared immunity from prosecution.

Rachel Melancon went to school for history and international studies, specializing in Western authoritarianism. She lives in the Deep South with her husband, a handful of animals, and her daughter.