by Jo Seck, 2018 Freedom for Immigrants Youth Justice Fellow

The U.S.’s approach to allowing deaf immigrants into our country has historically had ties to their perceived social desirability, eugenic worth, employability, wealth, reproduction and government dependence. Similarly, today deaf immigrants face commonly held notions and stigmas about their ability to contribute to society.

When looking at some of the earliest documentation of deaf immigrant cases, one can see patterns and scenarios that are all too commonplace today.

In the 1880’s the federal government began to enforce and regulate immigration; specifically, it excluded those migrants who were deemed “defectives.” Deaf immigrants in particular were turned away at U.S. ports because they were perceived to be “undesirable.” Deaf people could be viewed as carriers of defective genes, being too economically dependent, and a safety threat to the nation. Disability status was also more heavily scrutinized and stigmatized during the immigration process. With the influx of immigrants, forced sterilization through state eugenic laws, the suppression of sign language through forced oral education and lip reading, the institutionalization of the mentally ill and initiatives made to exclude disabled people from social and cultural participation fueled hate, intolerance, ableism and xenophobia¹.

In 1913, Morsche Fischmann, an ironworker who migrated from Russia, landed at Ellis Island hoping to join his brother and sister in New York. The Public Health Service at the time deemed him ineligible to land due to his deafness, and subsequently held a trial for him. Although the Bureau of Immigration in 1913 employed a large number of interpreters for spoken languages, interpreters of sign languages of the world were not available. Morsche was able to rely on his siblings to get his point across but it took him years to gain entry to the U.S. Fast forward to 1990, when Congress removed the provisions in immigration law that excluded people with disabilities but kept public charge provisions. Despite this reversal in policy, immigration officials can still deny a person entry into the U.S. because of the fear that they could likely become “public charges”². Public charges as defined by the USIC is “an individual who is likely to become primarily dependent on the government for subsistence as demonstrated by either the receipt of public cash assistance for income maintenance, or institutionalization for long term care at government expense².”

The same cultural conditioning that immigration officials held back in the day are still very much fabricated and integrated in how prejudice, bias, stigma and ableism still reverberate in the ways that deaf inmates are not on the same playing field as their hearing counterparts. The progress that has been made today is still is a reflection of the conditions that deaf inmates have had to endure in the past.

Deaf immigrants have to overcome more hurdles in a system that has become even more complex and harder to navigate.

Immigration detention centers today have still not taken the provisions and measures to ensure that deaf inmates are accommodated and provided with an interpreter. Immigrants come from all across the world seeking asylum, refuge and safety from political persecution, endless wars, extreme poverty and environmental crisis, yet the U.S. lacks a system to accommodate those that speak other forms of sign language. Each country has its own version of sign language, and there are many different ways to communicate in sign language around the world.

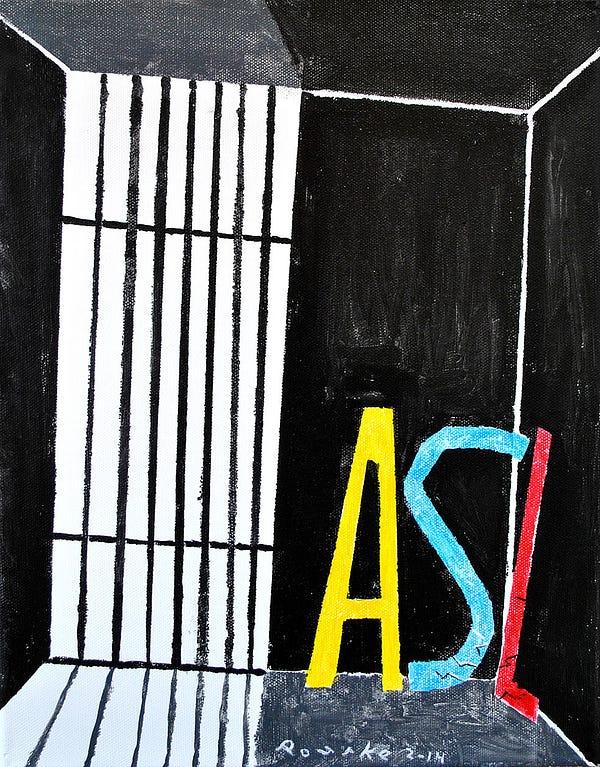

Although sign language may seem like a universal language, each region, territory and continent has vastly different ways of communicating and signing. American Sign Language (ASL) covers North America including Canada. And even though the British Australians speak English, their versions of sign language are strikingly different from ASL.

Even today, deaf immigrants are not guaranteed the right to testify on their own behalf. Judges and staff will often knowingly question deaf inmates verbally even though they cannot speak and/or lip read. Too, deaf inmates are more than likely handcuffed during a court proceeding, preventing them from expressing and conveying what they need either through sign language or through written communications. Providing interpreters is almost always elective, not a requirement, and is left to the discretion of the officials that work in the facility³.

In 2014, Abreham Zemedageghu, a deaf immigrant from Ethopia, spent six weeks in an Arlington, Texas jail in custody for allegedly stealing an iPad in an airport. He was routinely denied meals, medication and the ability to make a phone call while in jail. Because he could not read or write English, Zemedageghu was isolated and unable to communicate effectively with his other fellow inmates. In one such instance, Zemedagehu refused to sign medical papers he could not understand. After being stabbed in the arm with a needle, he found out after the fact that he was administered a tuberculosis test. During his stay, the Arlington jail did not make sure that Zemedagegehu had appropriate accommodations under the Americans with Disabilities Act and the Rehabilitation Act. The jail was also not equipped with hearing aids and telecommunication devices that would have made the process of filing a complaint and communicating easier to those outside of jail. He could have spoken to an attorney and family members but instead was isolated and subjugated to living a marginalized existence⁴.

Zemedagehu’s jail had a teletypewriter (TTY), which is not used that often anymore and was used to type messages in English that Zemedageghu rarely understood. Video phones are the preferred mode of communication among the deaf population; by comparison only an estimated 100,000 of around 1 million “functional” deaf individuals know how to use a TTY.

At the moment, the organization/advocacy group HEARD (Helping Educate to Advance the Right of the Deaf) estimates that there are 10,000 deaf people in jails or prisons nationally. There are no current estimates or approximations of the number of deaf individuals currently in immigration detention. Solitary confinement is used as a punishment if deaf inmates request accommodations. In some circumstances, officials can claim sign language elicits gang violence. If there are multiple deaf inmates, facilities will often separate them into different units and cells to avoid the risk of an uprising. Deaf individuals are also more prone to police brutality and violence both inside and outside detention facilities.

In another case, Rosario Maciel Avitia was held five months longer then she should have due to a bond opening up just days after her arrest. The reasoning that is given for the missed bond opportunity was not providing Rosario with needed accommodations, but in actuality was because of the lack of communication by the staff. But Avitia also had to deal with not having access to an ASL interpreter or other forms of assistance during her detention stay. She couldn’t understand important information about the jail before she was detained. And when she needed medical assistance for symptoms of depression, as well as for back and knee pain, her medication dosages were changed without her knowledge. Since her facility did not come equipped with a text telephone or videophone, she could not effectively communicate her problems with family members or disability advocates. HEARD put out a video shedding light on Avitia’s son, who was unable to contact his mother due to the outdated and lack of equipment at his mother’s facility⁵.

Avitia had also advocated for an interpreter for educational courses and religious services. And while weekly film screenings came with closed captioning, ICE staff refused to turn them on for her. In June 2016, Avitia sued ICE for denying her services, segregating her, and treating her differently than other inmates⁵.

The inability to communicate via phone also took a toll on a staffer at GLAD (Greater Los Angeles Agency on Deafness), who had to make 80-mile round trip visits to see Avitia in person⁵.

And this year, Francis Anwana, a 43 year-old deaf and cognitively disabled Detroit immigrant who had lived in the U.S. since he was 13, was told to appear for deportation on September 11. After public outcry and support in Michigan, he was granted a one-year stay of deportation. A local Congressman has introduced a bill in Congress to grant Anwana permanent legal residency⁶,⁷.

Other organizations on the ground are also paving the way to enact change on various levels. One such organization, DEAF VISA (Deaf Visitors & Immigrants for Self-Advocacy), seeks to bridge the gap and connect communities, empower individuals, affirm their strengths and combat social isolation and systemic barriers to communication, education, economic opportunity and independence⁸. The stated mission of another organization, Deaf Refugee Advocacy, in Rochester New York is “… to collaborate and serve as a bridge with current organizations and agencies to ensure inclusion of Deaf refugees into our Rochester Deaf community and into general society by providing assistance as they strive to be self-sustaining neighbors while still retaining their own cultural heritage, identity, language, and religion.” The agency also seeks to help deaf refugees navigate and integrate into the local community without losing their practices, ways of life and traditions⁹.

Although individual victories and milestones have been met, there are still a vast amount of noncompliant and negligent ICE-run and for-profit CoreCivic- and GEO-run facilities that are not providing vital and necessary accommodations to deaf inmates to ensure their well-being and mental stability and to provide a social support system. Without sweeping implementations, oversight, enforcement and legislation, there will still be rampant abuse and neglect at the hands of ICE towards deaf individuals. When more people can value the lives of deaf individuals and advocate for change and hold officials accountable for their treatment then we can begin to end the vicious cycle of abuse and discrimination that threatens to spiral out of control.

Jo Seck is a 2018 Freedom for Immigrants Youth Fellow. They are a graduate of Stony Brook University with a Bachelor’s Degree in Women, Gender & Sexuality Studies. While at Stony Brook, Jo was involved as a Research & Teaching Assistant in the Women, Gender & Sexuality Studies Department as well as a member of the Social Justice League, LGBTA, and as a founding member of the United Nations Association SBU Chapter. They spent their last semester as an Intern with the Queer Detainee Empowerment Project (QDEP) as well as a HYA Youth Advocate Fellow at the Hetrick Martin Institute (HMI). As an extension of a semester project for a class, Jo helped curate Take Back The Fight: Resisting Sexual Violence From The Ground Up Exhibition At The Interference Archive in Brooklyn in the summer of 2017. They also were a Writing & Development Intern for the Northeast Queer College Collective (NEQCC) in 2017. Currently Jo is currently pursuing a Masters of Social Work Program at the University at Albany-SUNY.

¹ Baynton, Douglas C., ‘‘The Undesirability of Admitting Deaf Mutes’’; US Immigration Policy and Deaf Immigrants, 1882–1924.” Sign Language Studies6.4 (2006): 391–415.

² https://www.uscis.gov/greencard/public-charge

³ https://www.themarshallproject.org/2018/10/18/the-isolation-of-being-deaf-in-prison

⁵ https://ocweekly.com/santa-ana-settling-with-deaf-immigrant-detained-by-ice-7967327/

⁶ http://www.michiganradio.org/post/ice-grants-one-year-stay-deportation-deaf-disabled-man